Torture and confession

The use of torture to gain a confession was illegal in England, but not so in Scotland, which is why the Scottish witch-hunts were so brutal – particularly so, of those in Fife. In fact, towards the end of the 17th century, the English were becoming aware of just how brutal their northern compatriots were in relation to the torture meted out to so-called witches. In 1652, one English newspaper, the Mecurius Politicus, wrote:

“The re-telling of the barbarous treatment suffered by the suspected witches serves not only “enough for reasonable Men to lament upon” but makes the English audience aware of the differences between the Scots and themselves.”

Sleep deprivation called ‘warding’ was widely used in Scotland, in conjunction with prodding, poking with pins, pulling of fingernails, and being jailed in cold and damp confines with no warmth. After being kept from sleep for this length of time, a confession due to hallucination, delirium, and hunger was highly likely. I will leave such devices as ‘the Boot’, and ‘the Bridle’ to your own imaginings as I have no stomach to write about such gruesome things. Other forms of torture included hot tongs, thumb tacks, screws, pinchers etc.

If a confession was still not forthcoming, the Presbytery would send for a witch-pricker to deliver ‘brodding’. The witch-pricker claimed to be able to find the mark of the Devil on a suspect’s body using certain long sharp implements, and his evidence often sealed the fate of the victim.

Also operating were witch-finders who claimed to be able to look into a person’s eyes and tell if they were a witch or not. Men of these vocations were seen as respectable in their communities and held some degree of social status, even gaining civic honours for their work. John Kincaid and George Cathie were two notable witch-prickers and very well paid ones. Chillingly, the Reverend Allan Logan of Torryburn was notorious for his skill in identifying so-called witches and during church services was known to pin-point a terrified parishioner from the pulpit and shout, ‘You witch-wife, rise from the Table of the Lord!’ On fleeing, the accused woman was then arrested.

After days of sleep deprivation and warding, an often semi-conscious victim would have her

confession mumbled to her by an interrogator and the sagging of the former’s head was taken as an affirmative response and indication of guilt. All roads lead to death from that point, except for some cases where a victim could call on someone with influence or power to save them.

Culross plaque on the Fife Witches Trail

Torryburn, Fife

Torryburn is a village in the district of Dunfermline and lies on the north shore of the Firth of Forth in Fifeshire. In the 1600s it was predominantly a mining village but also had outlying salt pans, so coal and salt were exported through its busy port; trade thrived between the Forth port villages and the Lowland counties. Torryburn served as the port town for Dunfermline, the capital of Scotland from 1043-1436. A church originally built in 1616 still stands as a place of worship today (some reconstruction took place in the 1690s and later), beside the burn of Torrie.

Fife was the epi-centre of the most brutal witch hunts and persecution, which accelerated between mid-16th to early 17th centuries. This was largely due to the aforementioned brand of religious fanaticism, but also a period of illness/disease that was prevalent in children and the use of healers. If your child died, it was easy to blame the healer.

Torryburn’s most infamous victim of these witch hunts was Lillias Adie, who after weeks of imprisonment and unrelenting torture, died before she could reach trial. She was buried on the shore ‘within the sea-mark’, at Torryburn in 1704, under a weighty slab of stone.

Lilias Adie Grave slab, courtesy of Ronnie Collins.

Torryburn’s most infamous victim of these witch hunts was Lillias Adie, who after weeks of imprisonment and unrelenting torture, died before she could reach trial. She was buried on the shore ‘within the sea-mark’, at Torryburn in 1704, under a weighty slab of stone.

In Scotland, most witches were strangled at the stake and then burnt, so do not have a resting place. Information about the relationship between Lillias Adie and Grissell Anderson appears further on in this article.

Map of Dunfermline Presbytery. No. 9 - Torryburn Parish. (Source: Macdonald 1997, p. 164)

Grissell Anderson (1628-1666)

Grissell Anderson was born on 11 January 1628 in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. She was the youngest of four surviving children born to John and Martha Anderson (nee Mastertoun). Her siblings were: Bessie (1619), John (1621), and Marjory (1625).

On 2 December 1646, Grissell married James Whyte (1624-1665), also from Dunfermline; she was 18 and he was 22 years old. They had two known children: Thomas (1647) and Agnes (1650-1699) – both born in Dunfermline. It is through Agnes that we are descended. In 1665 Grissell’s husband died; her father also deceased the same year.

The following year, widow Grissell was arrested on suspicion of being a witch and kept ‘warded’ in the Torryburn tolbooth (gaol) for a period of five days and five nights. With her were six other female suspects from Torryburn – they became known as the ‘Seven Witches of Torryburn’.

Some fifteen years earlier, an accused woman named Issobell Kellock had been sent to trial on 13 June 1649 in Dalgety Bay, Fife and burnt at the stake on 1 July 1649 (#2543). I believe she may have been Grissell’s mother in-law (that is, the mother of James Whyte). As happens even today, traditions and practices are passed down in families – handed on from mother to daughter and so forth.

The Seven Witches of Torryburn

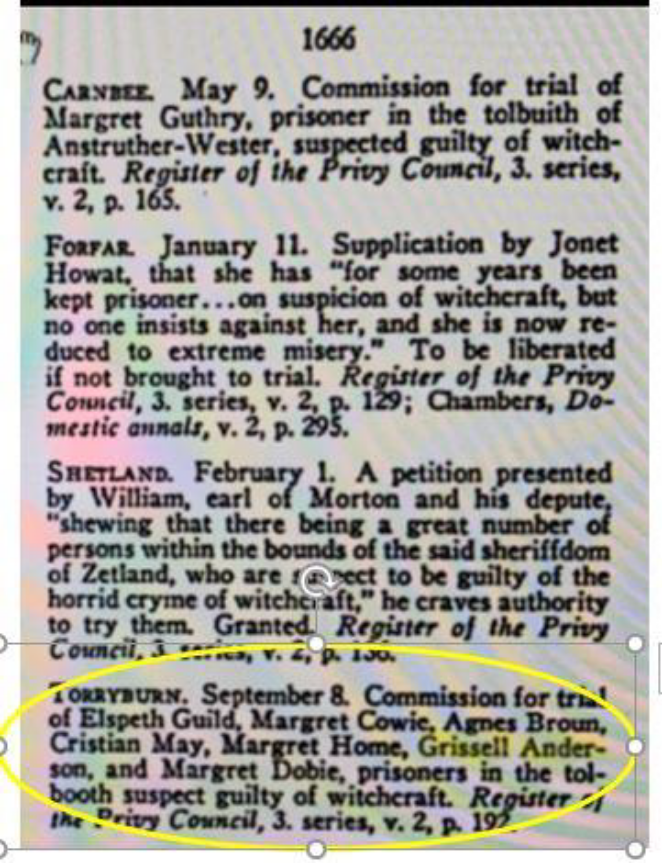

Extract relation to the trial before Privy Council of Scotland of Grissell Anderson and companions.

Source: RPC, 3rd Series, Vol. 2, pp.192-193. Purchased RPC e-file from Tanner Ritchie Publishing, Ontario, Canada 30/07/2020.

Grissell Anderson, Agnes Broun/Brown, Margaret Cowie, Margaret Dobbie, Elspeth Guild, Margaret Horne, and Christian May became known as the ‘Seven Witches of Torryburn’. Commissions for them to go to trial before the Privy Council of Scotland were issued on 8 September 1666. (Grissell’s case #1844). We do not know if the group had priorly confessed, but we do know that torture to procure a confession came before the granting of a trial commission. It was the Church that used torture to extract a confession and not the civil magistrate’s court. We can therefore feel assured that Grissell’s torture (as described in parts above) was at an end… apart from her final end.

Grissell Anderson

Agnes Broun/Brown

Margaret Cowie

Margaret Dobbie

Elspeth Guild

Margaret Horne

Christian May

Grissell and her six female companions were sentenced to death before the Privy Council.

Valleyfield plaque on the Fife Witches Trail

Grissell’s death

Two months later, Grissell Anderson was strangled and burned at the stake – it was Michellmass Day, 11 November 1666. We know the fate of her and her co-accused from the memoirs of Lady Halkett (Anne Murray), a courtier’s daughter and widow of a laird who lived in Dunfermline (refer Figure 4). She was a devout Episcopalian and wrote in her diary about many aspects of her religion and other interests. She was herself a part-time healer in the community, using herbs and various ointments, backing this up with prayers for the sick. She was incredibly careful not to use any charms and knew just how far to go with her healing. In other words, she understood the boundaries of her religious beliefs and the superstitions of the day. From her many writings, we glean that she and other intellectuals were out of sympathy for witchcraft executions. In their judgement, they were not just a tragic mistake but scandalous acts.Times were starting to change; the period of Enlightenment (the Age of Reason) was beginning to dawn. But it would be too late for Grissell and her co-accused. In 1688 Lady Halkett, looked back and reflected on her notes from November 1666 (22 years earlier) and records:

‘Upon Michallmas day 7 were burnt for Witches at Toriburne And by what hath since hapned itt may be concluded they died inocent as to that guilt for none that condemned them hath (likely) to leave anything behind them to preserve there memory.’

Apart from the innocence of the victims, Lady Halkett’s condemnation of these executions was based around her observation that God had not allowed the persecutors of witches to prosper, which lead her to assume their guilt. Lady Halkett was a witness to horrendous crimes against innocent women and men, and her voice tells us how it was, hundreds of years later.

Torryburn plaque on the Fife Withces Trail

Lillias Adie and Grissell Anderson – The connection

Project Gutenberg (i.e. the ‘Minutes and Proceedings of the Kirk-Session of Torryburn Concerning Witchcraft, and the Confession of Lillias Adie’), reveals that there was a connection between Lillias Adie and Grissell Anderson which went further than just being Torryburn women. It is worth noting that Grissell was born in 1628 and Lillias in 1640; the former being senior by some twelve years.

These Kirk-Session ‘Minutes and Proceedings’ first mention Lillias Adie on 30 June 1704, during an interrogation of her relating to a woman named, Jean Bizet, and others.

Lillias’ connection with Grissell Anderson is revealed from her lengthy interrogation between 31 July – 2 August 1704. In what appears to be an eventual confession, Lillias described how she had been invited to ‘meet the devil’ at her first meeting at Gollet (near Torryburn), ‘at the time of harvest before the setting of the sun’. Lillias named Grissell Anderson as the one who had summoned her to her second meeting, ‘at about Martinmas’ and where there had been ‘twenty or thirty whereof none are now living but herself’. This woman is highly-likely ‘our’ Grissell who had been dead nearly 40 years by then; clearly Lillias was recalling her first encounters in her late teens. A further encounter with Grissell follows:

August 2nd, 1704 ‘Lillias declared before witnesses, that Grissel Anderson invited her to her house on that Lammas day, the morning just before the last burning of the witches. Grissel desired her to come and speak with a man there; accordingly she went in there about day-break, where there was a number of witches, some laughing, some standing, others sitting, but she came immediately away, being to go to Lammas fair; and several of them were taken shortly after, and Grissel Anderson among the rest, who was burnt, and some of them taken that very week.’

Chillingly (on a personal level), Lillias Addie had recalled the last days of Grissell Anderson.

It is said in many biographies/articles, that Lillias Adie did not reveal any new names to her torturers, only those who had already deceased. However, the Kirk-Session Minutes and Proceedings appear to state otherwise. She mentioned the names of Elspeth Williamson and Agnes Currie who were both living and imprisoned at the time:

At Torryburn, August 19th, 1704 Lillias Adie confessed, that after she entered into compact with Satan, he appeared to her some hundred of times, and that the devil himself summoned her to that meeting which was on the glebe, he coming into her house like a shadow, and went away like a shadow; and added, that she saw Elspeth Williamson and Agnes Currie both there, only Agnes was nearer the meeting than Elspeth, who was leaning on the church-yard dike with her elbow.

August 29th, 1704 Lillias Adie declared, some hours before her death, in audience of the minister, precentor, George Pringle, and John Paterson, that what she had said of Elspeth Williamson and Agnes Currie,was as true as the Gospel; and added, it is as true as the sun shines on that floor, and dim as my eyes are, I see that.

From reading these interrogation files, I believe it was probably not on Lillias’ account that Elspeth and Agnes were arrested; but under extreme duress she did speak against them. On the third day of September 1704, Lillias Adie was buried on the shore at Torryburn.

Remembering Grissell

Grissell Anderson met her death unaware that others would carry the knowledge of her innocence down through the next centuries. She did not live to see societal change and the outlawing of witch hunts. Sadly, she never got to hold her children again… she didn’t live to see her 15 year old daughter marry and have a family of her own… and she never knew where the winds carried her ashes. And she could never know that 350 years later, her descendants would go looking for her, and on finding her, embrace her tightly and seek to right the grotesque injustice she and many others had suffered.

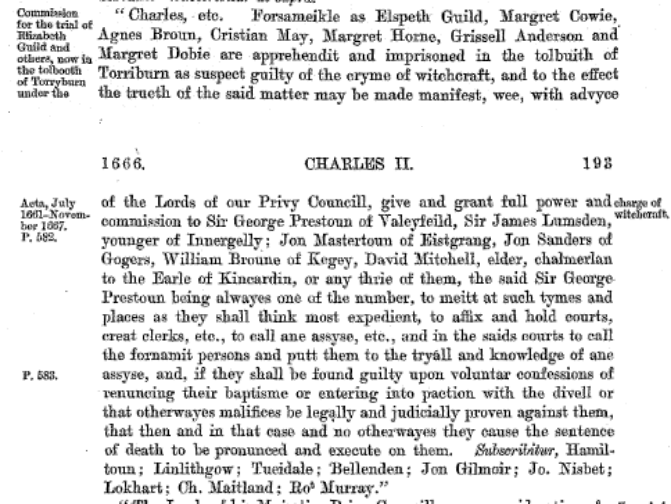

Figure 4: Lady Halkett’s meditations provide confirmation of the execution of the Seven Witches of Torryburn.

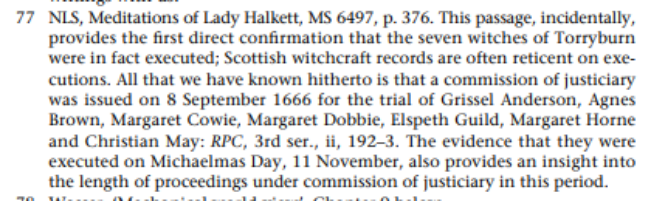

Figure 5: Further information on the fate of the Seven Witches of Torryburn (Macdonald 1997, pp.205-6)

Curio Hunters

Joseph Neil Paton was a collector of artefacts associated with witchcraft and he promoted the ‘science’ of phrenology – a belief which suggested that an individual’s character could be learned from a study of their skull.

Paton paid for graves to be robbed across Fife. He acquired the skull, ribs and femur of Lilias Adie and sold them to medical students at St Andrews University.

Robert Baxter Brimer who had been involved in robbing the grave of Lilias Adie in 1852, presented a walking stick to Andrew Carnegie the Industrialist and philanthropist made from the wood of Lilias’s coffin. The walking sticking can be seen in the Carnegie Birthplace Museum in Dunfermline

West Fife Villages Heritage Network facilitated the delivery of this project. Thanks to the following funders Fife Council, Heritage Lottery.